‘It isn’t a villa but it is our home. I have lived here all my life.’

Qusai Burqan, Silwan

When EAs were called to attend a demolition taking place in the district of Wadi Yasul in Silwan, just below the Old City Walls in East Jerusalem, they were made aware that over 60 Palestinian houses in the area had been served demolition notices by the Israeli military. Two properties lay in ruins already, and neighbours were worried that they might be next on the unpredictable, no-advanced-warning list to demolish, because all of the houses here had been built without Israeli planning permission, which is near impossible for Palestinians to obtain.

‘Ever since 1967, planning policy in Jerusalem has been geared toward establishing and maintaining a Jewish demographic majority in the city. Under this policy, it is nearly impossible to obtain a building permit in Palestinian neighborhoods’

We were invited for refreshments into another Palestinian home, close to one of those demolished that morning. The house was one of two on the plot, each lived in by brothers from the Burqan family, their wives and children. The young men’s father had built the first house on the plot some thirty years ago on land the family had owned for generations, since the time the area was under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Both houses, and the animal shelter for the family’s small flock of sheep, had also been served demolition notices.

Qusai Burqan showed us round the family home. ‘It isn’t a villa,’ he said, ‘but it is our home. I have lived here all my life’. A large TV screen dominated the living space, and a photograph of his father smiled benignly down, next to a photo of another brother who was to be married the following week. In a scene all of us would recognise, we talked to Quasi’s brother standing next to the fridge in the kitchen, with the oldest child’s homework timetable on the fridge door.

EAs visit the home of Quasi Burqan, who has been issued with a demolition order

Qusai explained that they had been visited on more than one occasion by Israelis from a settler organisation who had offered to buy the house and the land. One had offered a blank cheque saying, ‘just fill in the amount you want and leave’. ‘We cannot leave,’ said Qusai. ‘It is our land, our home, our community’.

‘My mother only hopes that we can enjoy the wedding before the house is demolished’

Qusai Burqan, Silwan

The mother’s wish was granted. The wedding took place before the demolitions, but when we called again two weeks later, the home in which we had been served juice lay in ruins. The red sofa on which we had sat, looking at the family photos, lay under the rubble of the demolition. Qusai’s brother’s house and the shelter for their sheep had also been demolished.

Qusai explained that the demolition team had arrived early in the morning with a large number of soldiers who had surrounded the property. The bulldozer had broken down shortly after it had started its destructive work, but during the five hours it took to repair, the family was not allowed to enter their own home to remove their possessions. The bulldozer even destroyed a small plastic shed which contained the children’s toys and bikes, even though this was not part of the demolition order, and despite the pleading of the family. After both houses and the animal shelter had been reduced to rubble, the bulldozer rumbled down the drive, partly destroying a retaining wall, some olive trees and the large steel gate, not because it was blocking the way – it was wide open said Qusai – but just ‘because they can do what they want’.

We visited the office of BIMKOM, an Israeli human rights organisation formed in 1999 by a group of professional architects and planners in order to better understand the planning issues faced by the residents of East Jerusalem in general, and in Silwan in particular. ‘Planning is a tool of the occupation,’ said Alon of BIMKOM, ‘which the Israelis have used with great effect. You need to remember that all of this area of East Jerusalem has been unilaterally annexed by Israel – it is a line on the map that impacts on planning regulations – but it isn’t recognised as being part of Israel by the majority of the international community’.

He continues, ‘other Israeli policies have negatively affected Palestinians’ ability to plan and develop their communities and enjoy the services they are entitled to, further undermining their presence in the city. In East Jerusalem, a restrictive planning regime makes it impossible for Palestinians to obtain building permits, impeding the development of adequate housing, infrastructure and livelihoods.’

‘It is important to stress that the obsession with the demographic balance is not about creating an actual balance between the different population groups that make up the mosaic of the population in Jerusalem, but explicitly for the purpose of maintaining the demographic advantage of one group – Jews.’

Alon, BIMKOM

After the 1967 war and the occupation of the West Bank by Israel, significant parcels of land were added to the municipal area of Jerusalem. This increased the geographic area of Israeli-controlled Jerusalem from 38,000 dunam (equivalent to 1000 square metres) before 1967 to 109,000 dunam (later on, the municipal borders of the city were expanded westward as well, and today the area of the city is about 126,000 dunam). This rapid and expansive growth was done, according to BIMKOM, ‘with the objective of strengthening Jerusalem’s status as a major Israeli city, as the capital of Israel, and as a global centre for world Jewry’.

Since then, planning and development policy in East Jerusalem has been dictated by two complementary principles: demographic balance and territorial expansion. In other words, planning and development policy in the city aims at ensuring a Jewish majority in the city by designating the vast majority of available areas in East Jerusalem for the Jewish population. This has the effect of establishing Israeli-Jewish territorial contiguity at the expense of Palestinian territorial contiguity and development in the Palestinian neighbourhoods.

Alon of BIMKOM explained, ‘We should keep in mind that while the state of Israel and the vast majority of the Israeli-Jewish public consider East Jerusalem to be an inseparable part of Israel, neither the Palestinians nor the majority of the international community recognize Israel’s de facto annexation of the areas conquered in 1967. East Jerusalem is viewed as occupied territory, and the Israeli neighbourhoods built there are “settlements” to all intents and purposes, which are illegal under international law. Furthermore, despite Israel’s portrayal of Jerusalem as a united city, with the rare exception, Palestinian and Jewish-Israeli populations live in completely separate neighbourhoods – the demolition of houses in Silwan is to create a new Jewish area at the expense of the Palestinians who live there. The struggle is about demography.

‘It is important to stress that the obsession with the demographic balance is not about creating an actual balance between the different population groups that make up the mosaic of the population in Jerusalem, but explicitly for the purpose of maintaining the demographic advantage of one group – Jews. In 1967, at the end of the war, the ratio of Jews to Arabs in Jerusalem was 74:26. By the end of 2012 the ratio of Jews to Arabs was 61:39, and trends in both natural population growth and migration show a consistent rise in the proportion of Arabs in the city. The practical implication of the obsession with the demographic balance is active government intervention to change existing trends, or at least to try and restore the ratio that existed at the end of the 1967 war. The planning system in Jerusalem is mobilized for this mission, and the plans drawn up for the Palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem, are guided by this principle.’

It is a principle that has left Qusai and his family, and his brother’s family, without homes.

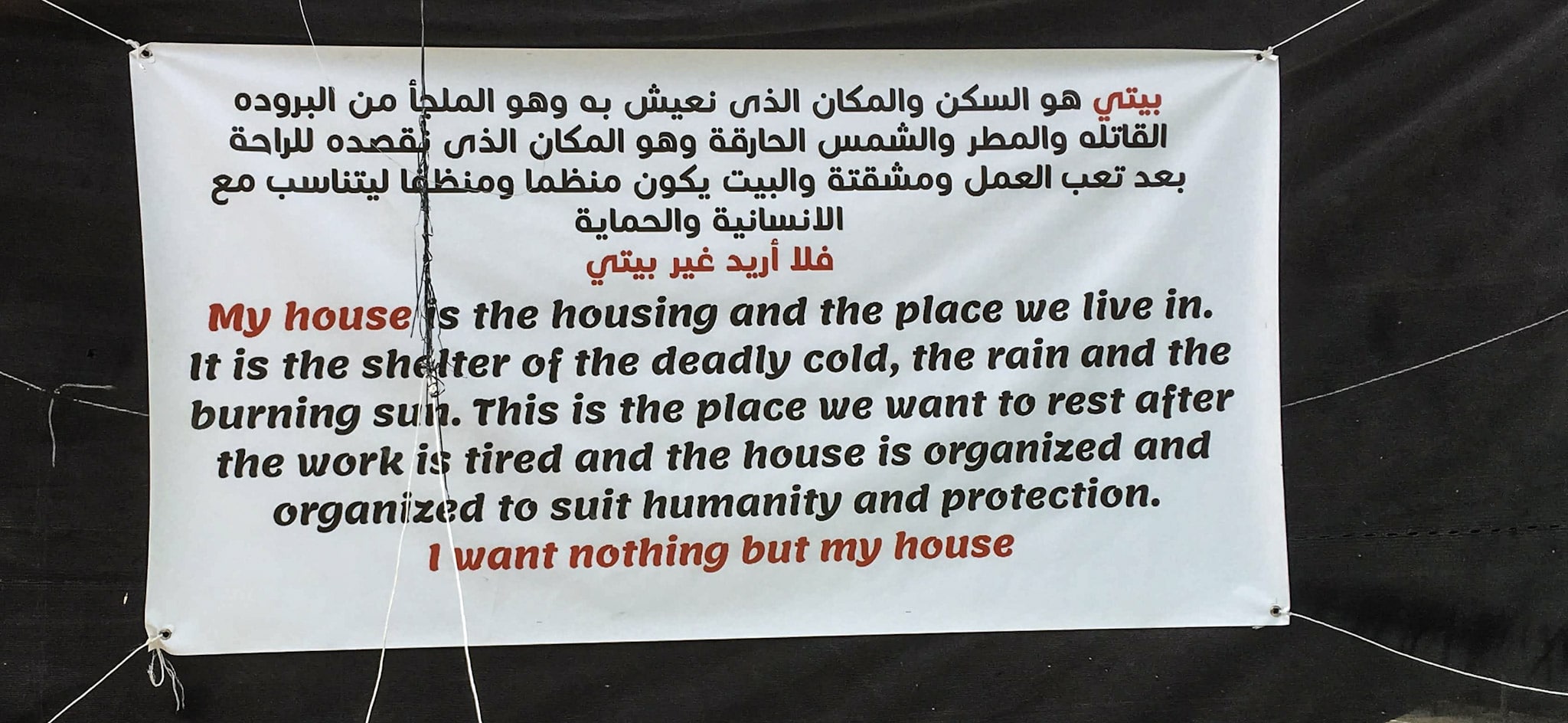

A sign in the community tent in Wadi Yasul, Silwan, East Jerusalem, days after the demolitions had taken place