‘The use of technology at checkpoints like Qalandia speeds up the time needed to check documents but it also facilitates control. Palestinians (with few exceptions) are now required to use biometric magnetic cards whenever they go through a checkpoint, which means their movements can be tracked.’

EA Belinda

The State of Israel recently spent tens of thousands of shekels modernising checkpoint facilities, a move which they insist will ‘improve the fabric of life’ for Palestinians.

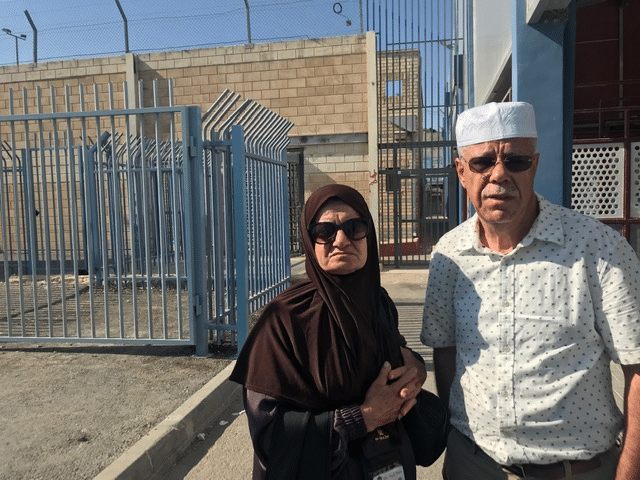

The Qalandia checkpoint in northeast Jerusalem is the main checkpoint between Jerusalem and Ramallah and therefore between Jerusalem and the northern West Bank. Thousands of Palestinians pass through it every day. Most are commuting to work though there are many reasons for needing access to Jerusalem, such as access to medical care and weekly worship in the churches and mosques. The numbers passing through increase greatly during Muslim holidays when tens of thousands of worshippers seek to cross the checkpoint to visit the holy places of the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Before Palestinians reach the checkpoint, they must apply for a permit from the Israeli authorities, through a system which is often bureaucratic and unpredictable (Machsom Watch). There are over 100 types of permit and success in obtaining them is not guaranteed. ‘Only Palestinians are restricted in this manner, while settlers and other civilians – Israeli and foreign – are free to travel’ (B’Tselem).

The Qalandia checkpoint was first established in late 2001. A comprehensive border control infrastructure was developed over the following years, especially after the construction of the Separation Barrier which Israel built to separate the West Bank from Jerusalem and Israel. The route of the separation barrier, built in large parts on occupied Palestinian land, was ruled to be illegal by the International Court of Justice in 2004.

Qalandia checkpoint became notorious for the inhumane way it ‘processed’ human beings and for the metal cages and turnstiles that contained them.

The new checkpoint facilities, opened this spring, have resulted in faster crossings and virtually no queues. Six metal detector stations and 27 automatic ‘speedgates’ have replaced the five checking stations where permits were checked manually. The gates are operated with a biometric or ‘magnetic’ card, which Palestinians have to obtain from one of the Israeli District Civil Liaison Offices in the West Bank and Jerusalem. They need to apply in person, pay a fee and have prints taken of their hand and fingers as well as a photograph. The checkpoint gates are operated by means of a card reader and a facial recognition screen.

When the upgraded facilities at Qalandia were shown to the press earlier this summer, the Israeli authorities emphasised the benefits to Palestinians. The goal is to ‘improve the fabric of life’, according to the deputy head of COGAT, the Defence Ministry’s department responsible for coordinating government activities in occupied Palestine. A video on COGAT’s website highlights the benefits to Israeli employers of Palestinian workers getting to work on time without waiting at the checkpoint, sometimes for hours.

The modern machines and piped music are presumably meant to improve the experience of passing the checkpoint. A wheelchair ramp is provided which leads from the pavement in front of the checkpoint building up to the level of the entry gates. Reaching the pavement however involves first crossing the four lanes of traffic for the vehicle checkpoints and then navigating rough terrain and a number of curbs.

We’re told by locals and former EAs that the old checkpoint facilities were well-known for the poor toilet facilities. The same ones are still in use. Machsom Watch, an organisation of Israeli women which has monitored the checkpoints since 2001, publishes reports on what it witnesses. A recent report is headed: ‘Permit holders move quickly, however the checkpoint plaza is neglected, the toilets are filthy and dirt and trash is everywhere.’

‘The physical developments of the checkpoints is not the interesting part…What no one is talking about is who is allowed to pass and who is not.’

Machsom Watch