Sheikh Eid lives in Nabi Samuel, a Palestinian village perched high in the hills of northwest Jerusalem. On one side of his home, he can see the city centre just four kilometres away — yet he is forbidden from entering it. From the other side, he looks toward Ramallah, across the Separation Barrier in the occupied West Bank — but reaching it is also difficult.

View of Jerusalem from Nabi Samuel across the illegal settlements

Nabi Samuel sits on the edge of Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries, in a strip of land known as the ‘seam zone’. This area lies between the Green Line— the internationally recognized border between Palestine and Israel —and Israel’s Separation Barrier, a 700km-long concrete wall and fence system built to divide Israel from the West Bank. Although Sheikh Eid’s home falls within Jerusalem’s boundaries, he holds a West Bank ID. This document, issued by the Israeli authorities, does not allow him to enter the city.

‘People have taken that road occasionally to find work in the city,’ he says, pointing to the road that leads left into Jerusalem. ‘But if they are caught, they are put into prison.’

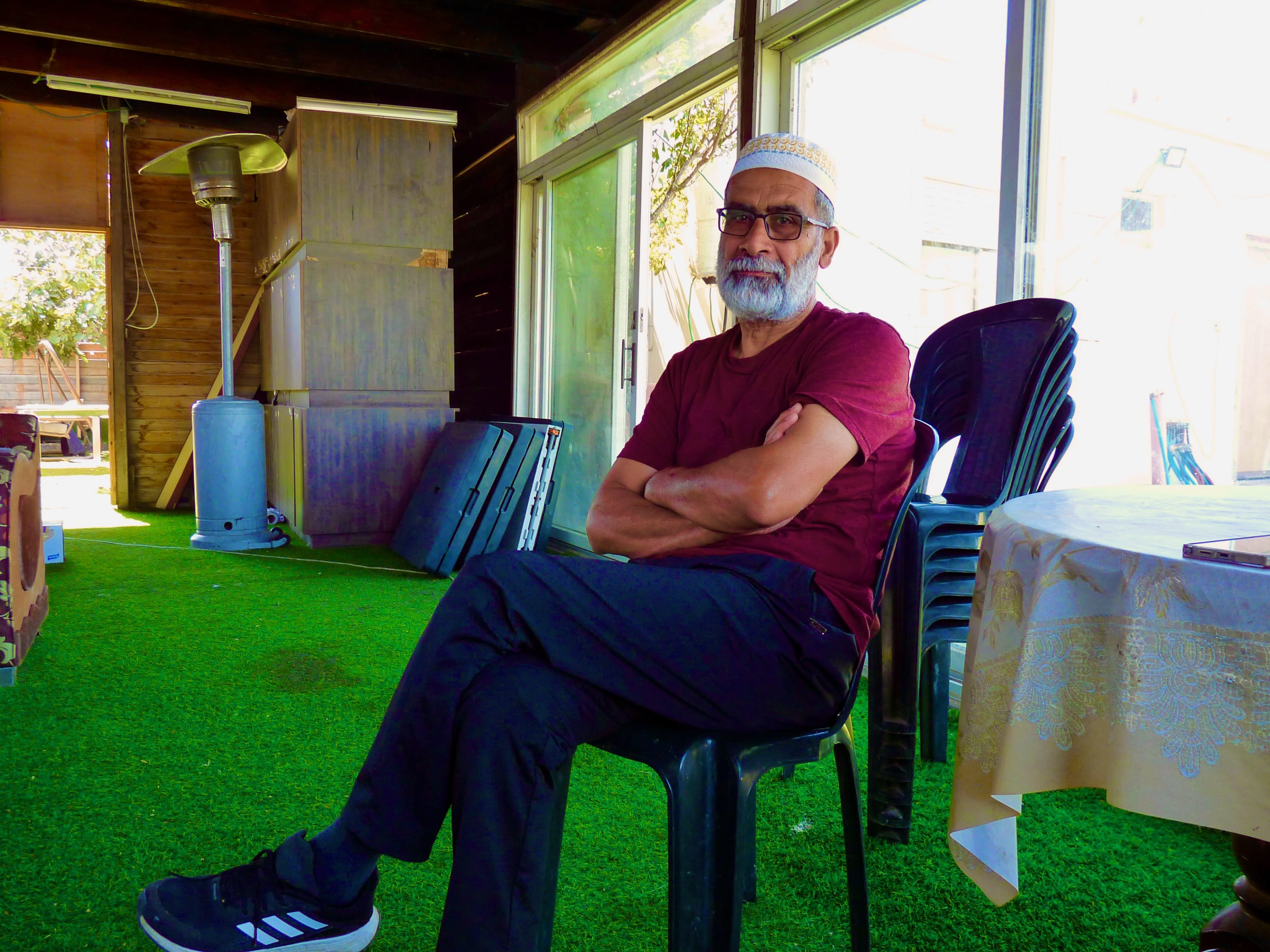

Sheikh Eid, Nabi Samuel

Sheikh Eid sitting in his home, Nabi Samuel

‘Prison’, in this case, means administrative detention — indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial, a practice illegal under international law. His own son was detained for four months.

Most Palestinians living in occupied East Jerusalem hold a different legal status from those in the West Bank. The Israeli state’s permit regime determines who may live, work, access healthcare, visit family or worship in Jerusalem. This system is enforced through a matrix of control: the Separation Barrier, nearly 1,000 military checkpoints along and within the West Bank, and a network of roads designed to serve Israeli settlers, living illegally on Palestinian land, while restricting Palestinian movement.

Entrance to Nabi Samuel archeological park

The entire infrastructure and permit system creates a two-tiered system of apartheid where Israelis have freedom of movement and access, while Palestinians face severe restrictions.

‘The continuation of discriminatory policies in East Jerusalem has led to a decline in Palestinian residency. ACRI continues to protest these racist policies, and the home demolitions and forced relocation that result.’

East Jerusalem | Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI)

Nabi Samuel is one of 16 Palestinian communities covering around 55 square kilometres in northwest Jerusalem where around 70,000 people live under a regime of complete isolation. Although these villages fall within Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries, their residents are denied Jerusalem IDs. The Separation Barrier was built around the villages splitting them into two enclaves connected only by a dangerous, poorly lit tunnel. In September 2025 alone, four people died using it. The main road on top is kept for Israelis only.

Driving between the Separation Barrier to enter the tunnel connecting the Palestinian villages

Since the 1970s, successive Israeli governments have enacted laws that aim to promote and maintain a Jewish majority in the city of Jerusalem. The practice of severing these villages to push their residents into the West Bank supports Israel in enforcing this objective. All the residents’ agricultural land has been confiscated or is behind the Separation Barrier.

The residents of Nabi Samuel are cut off from both directions. They cannot enter Jerusalem, and their families and basic supplies from the West Bank cannot easily reach them either. Sheikh Eid’s daughter-in-law, Faada, who moved to the village to marry told us:

‘We’ve been married 8 years. In that time my parents have been able to visit me twice. The last time they waited all day at the checkpoint and in the end had to give up.’

Faada, Nabi Samuel

In September this year, Israeli authorities formally closed off the entire area. They issued Palestinians ‘Israeli movement permits’ stating that the area they reside in is Israel but paradoxically, those same documents forbid them from entering Israel. They are effectively trapped in their own homes. The consequences can be deadly. Sheikh Eid recalls the day his brother Ayed, fell from the roof of the mosque – the paramedics who arrived refused to take him into the city as he didn’t have the right ID. They called a West Bank ambulance, but it could not reach him through the local checkpoints. He died.

Nabi Samuel’s religious significance as the burial place of the prophet Samuel has also been used as a way to remove Palestinians from their land. In the 1970s, the original Palestinian village on the site was destroyed and in 1995 the entire village and most of the residents’ land was designated a national park of archaeological interest.

Israeli NGO Emek Shaveh, which was set up to challenge those who use archaeological sites to dispossess disenfranchised communities in Israel and Palestine, and has tracked the history of the designation of the site, states not only is there no evidence of any association to the 11th century prophet, but that:

‘[The village was] not demolished in order to promote an archaeological agenda, but out of the IDF’s aspiration to control a strategic location that overlooked the West Bank and north Jerusalem. Today, however, the excavations and the tourist site are obviating any possibility of the residents ever returning to their village.’

Sheikh Eid spoke about the moment his home was destroyed in 1971:

‘When our house was destroyed, our family of 6 was allocated one room with a kitchen and bathroom. My father wanted additional living space, but every time they put up a new structure it was demolished. Since then, we’ve had 28 demolition orders for agricultural and living structures of which 12 have already been executed.’

Sheikh Eid, Nabi Samuel

Sheikh Eid’s home

Despite this hardship, Sheikh Eid’s wife Nawal is a teacher in the village and has worked tirelessly to set up women’s activities in the villages.

‘We cannot enter into Israel and we can hardly work in the West Bank. But we have to find ways to be resilient. We’ve supported women to raise chickens, but eggs are banned from the village so we had to smuggle in chickens. We are involved in bee keeping projects, but we had to smuggle the bees in through the mountains. We are trying to grow woodlands but we cannot bring small trees as they are eaten by the deer brought in through the national park and the larger trees are forbidden.’

Nawal, teacher, Nabi Samuel

Nawal in the school in Nabi Samuel

Daily life in Nabi Samuel is a fight for survival. The women’s centre has been demolished, the children’s playground has had a stop work order and now sits idle, their single sewage pit has had a stop work order and so they are now without a sewage system, the village car wash business has had all its equipment confiscated and every home has a demolition order.

A small primary school exists for the children in Nabi Samuel for around 80 pupils in the village where Nawal works as a teacher. Older pupils need to cross the checkpoints to attend the school on the other side of the separation barrier. If the authorities close the checkpoint, it could take two or more hours. Yet in spite of this isolation, the message that Nawal wants to stress is one of hope:

‘I want the children in my school to live in peace, like every other child in the world. Until my last day, I will continue to fight for them to have peace.’

Nawal, teacher

Abandoned children’s playground, Nabi Samuel

Take action to end apartheid.

1. The story of Nabi Samuel is part of a wider system of apartheid that the International Court of Justice has stated is illegal under international law and must ‘end as rapidly as possible’. Demand the UK and Irish government uphold the ruling and say no to the annexation of Palestinian land:

2. We need your help to keep this vital work going. Donate today to help us continue witnessing and standing in solidarity with communities in Palestine and Israel.

What does international law say?