Standing in Khan al‑Ahmar, it’s impossible not to feel the weight of what is at stake. Abu Khamis, the community leader, speaks with the authority of someone who has repeated the same warning for years. His Bedouin community sits just east of Jerusalem, on the road to the Jordan Valley in the occupied West Bank. For generations, Palestinian Bedouins have lived by herding animals in these valleys, their identity inseparable from the land. It is an ancient way of life that remains central to Bedouin history and culture.

Abu Khamis community leader, Khan al‑Ahmar

Khan al‑Ahmar is only one of 22 Bedouin communities — more than 10,000 people — now facing the threat of forcible transfer by Israeli government. If these communities are evicted, the prospects of a future Palestinian state risks falling with them.

View of Khan al–Ahmar village from the illegal settlements on the hilltop

The Bedouin communities in this part of Palestine are originally from the Negev desert in modern day Israel but were forcibly displaced in 1948 alongside 750,000 Palestinians in what Palestinians refer to as the ‘Nakba’ or ‘catastrophe’. These Bedouins now live in isolated valleys in the West Bank which has been occupied by Israel since 1967. On the horizon above the communities stands the illegal Israeli settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, founded in the 1970s and home to around 35,000 Israeli settlers, and a string of smaller settlements ranging from a collection of caravans to larger communities with full infrastructure.

Khan al-Ahmar school with view of Israeli settlement Maale Adumim in the distance

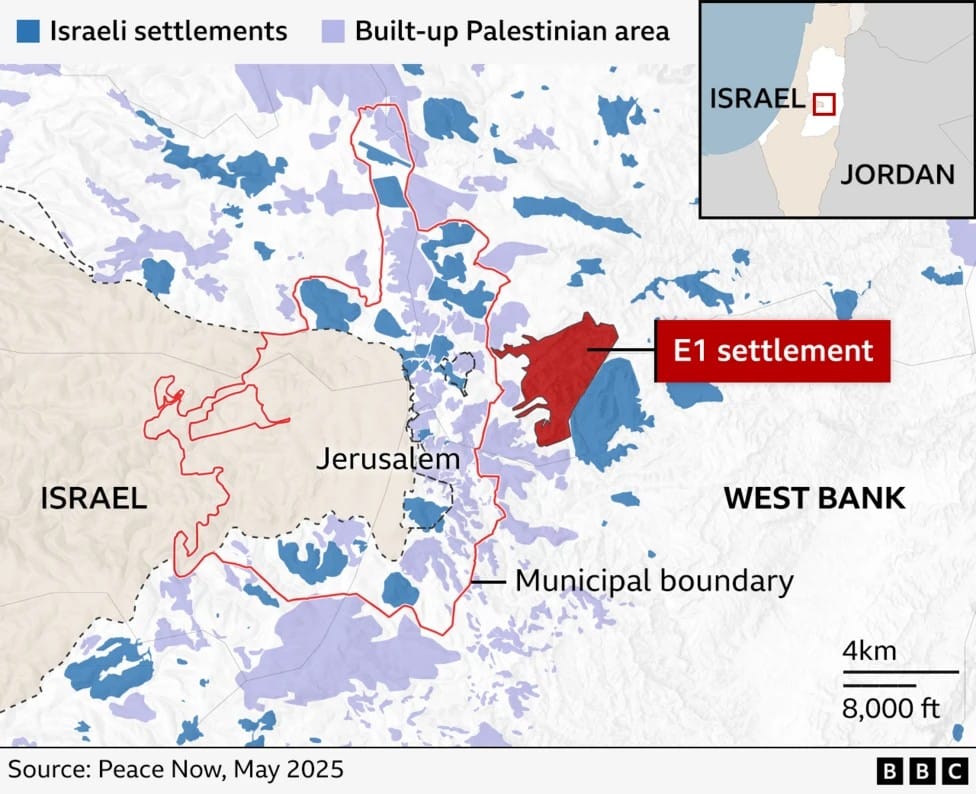

Now the Israeli government has started to implement long held plans to create a continuous built-up ring of Israeli Jewish-only settlements connecting Jerusalem with the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim and beyond to the Jordan Valley. The proposal, known as the E1 settlement plan, considered illegal under international law, will have severe consequences not only for Bedouin communities but for any future Palestinian state.

Map of E1 settlement, Credit: Peace Now

The Israeli cabinet has also allocated funds for a new segregated road system that imposes separate routes for Israelis and Palestinians. One key element is the expansion of a highway split by an eight‑metre concrete wall, channelling Palestinians onto restricted bypass roads while providing settlers direct, uninterrupted access to Jerusalem. The project would allow Israel to close off the central West Bank to Palestinian movement while enabling the illegal settlement bloc to function increasingly like a permanent part of Israel — paving the way for de facto annexation.

E1 segregated road in the West Bank which will be for exclusive use by Israeli settlers

“The advancement of this project is an existential threat to the two-State solution. It would sever the northern and southern West Bank and have severe consequences for the territorial contiguity of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.”

Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary General

Palestinian Bedouins are already among the most vulnerable communities in Palestine. They live in isolated areas that are often without proper road access and are restricted by checkpoints, severing them from essential services and markets, and preventing them from earning an income or grazing their livestock. These pressures directly undermine their herding‑based livelihoods, which depend on free access to pasture and water. Abu Khamis tells me how their situation has deteriorated significantly since in the past 25 years.

“Before 2000, we had 1,600 sheep and goats and 28 camels and would sell milk and meat products on Fridays in Jerusalem. But it is now forbidden to bring fresh products through the checkpoint and we have only 140 animals and no camels.”

Abu Khamis, community leader, Khan al‑Ahmar

This is not just about cultural survival — it is about food security for the entire Palestinian population. Bedouin herding communities contribute a significant share to the Palestinian market’s red meat and dairy supply, but this contribution has already fallen from around 25% to 13% over the past five years due to demolitions, forced displacement and settler violence.

“Since October 2023, West Bank Palestinian farmers have been repeatedly attacked, intimidated and threatened. These acts go beyond the resulting harm to the affected individuals and adversely affect the food security of the wider community.”

The Israeli government has been clear about their intent with the E1 project. Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who himself lives in an illegal settlement in the West Bank, said of the E1 project in August 2025:

“What we are privileged to do in this term is simply to erase the Palestinian state – later, with God’s help, officially, but first in practice, we are simply taking this idea off the table and establishing facts on the ground.”

Bezalel Smotrich, Israeli Finance Minister

In Khan al‑Ahmar, those “facts on the ground” are visible everywhere. Bulldozers are working day and night. Every home and structure carries a demolition order dating back to 2017. Even the primary school, built with EU support and serving 180 children, is under threat. To avoid immediate demolition orders, the school was constructed using tyres and compacted earth mixed with sheep dung, materials not classified as permanent structures under Israeli planning regulations. It is the only safe route to education for children who would otherwise cross highways under the watch of nearby settlers.

Khan al-Ahmar school walls built with tyres and organic material

Abu Khamis describes how new settler caravans are installed each week that look out over the school and threaten the communities.

“The settlers have been here for 10 months – they already have electricity and clean water. We cannot access the electricity grid. They drive through the village and make threats to the inhabitants. They set up in front of their homes and play loud music at night.”

Abu Khamis, community leader, Khan al‑Ahmar

International law is unambiguous on the legality of settlements: regardless of whether they are long established housing communities or isolated caravans – they are unlawful. In 2024, the International Court of Justice stated that Israel’s “policies and practices amount to annexation of large parts of the Occupied Palestinian Territory” and that Israel is “not entitled to sovereignty” over any of it. Yet the Israeli machinery of settlement expansion continues to move.

The situation in Khan al‑Ahmar is not isolated but reflects a wider pattern that continues the illegal occupation and threatens both the territorial viability of a Palestinian state and the food security of its population.

States have clear obligations under international law not to support or enable these measures.

Take action

-

Email your elected representative to demand they take action to stop Israel’s E1 settlement plan which could destroy the possibility of a future Palestinian state. It takes just 1 minute.

The need for solidarity and accompaniment is more important than ever. We can’t do this without you. Your support helps us maintain a solidarity presence in Palestine and Israel — witnessing human rights abuses and walking alongside communities under threat. Donate today.

What does international law say?